Buttonless buttons: the treatment of fabric-covered buttons in an 18th-century theatre costume

The jacket of a demi-caractaire costume, end of the 18th century, 21495_LRK, after treatment. Photo: Jens Mohr/SHM.

Recently, I had the chance to join SHM as a textile conservation intern. During my internship, I worked with, among others, costumes that will be displayed later this year in an exhibition on 18th-century theatre costumes at Livrustkammaren. A demi-character dance costume, worn by Hertog Carl, is part of the objects to be displayed (header). The costume consists of a sleeveless vest and a jacket of which the latter was particularly fragile. The jacket has very delicate gauze sleeves that were placed on a net during previous conservation. However, more on the re-treatment of these sleeves can be read in this blog. Another interesting aspect of the jacket is that only two of the twelve fabric-covered buttons were complete. The others either consisted of textile fragments without the wooden button or solely the textile base (fig. 2). To prevent further losses, it was decided to treat the buttons with loose fragments.

The different sizes of the fillings for each button. Photo by author.

As a result of the missing wooden core, a new filling had to be made to secure the fragments. It was decided that a soft filling would be best to keep the stress on the remaining textile limited. Different fabrics were compared on characteristics such as colour and stiffness. In the end, it was decided to use a beige/brown organza that would blend in with the fragments and the jacket. The textile was folded to create eight layers. The middle was then attached with a thread to keep the layers from separating. It was cut into a round shape and the size was adapted to each button. Some buttons needed a smaller infill than others, but it was attempted to keep the differences minimal to keep the row of buttons uniform (fig. 3).

The loose fragments of the left button were adhered to the organza filling. Photo by author.

A layer of 50% Lascaux 303 and 498 in equal parts was applied with a brush to the top layer of organza and left to dry. Following, the filling was sewn to the textile base of the button to keep it in place. The fragments were then adhered to the filling with a heated spatula (fig. 4).

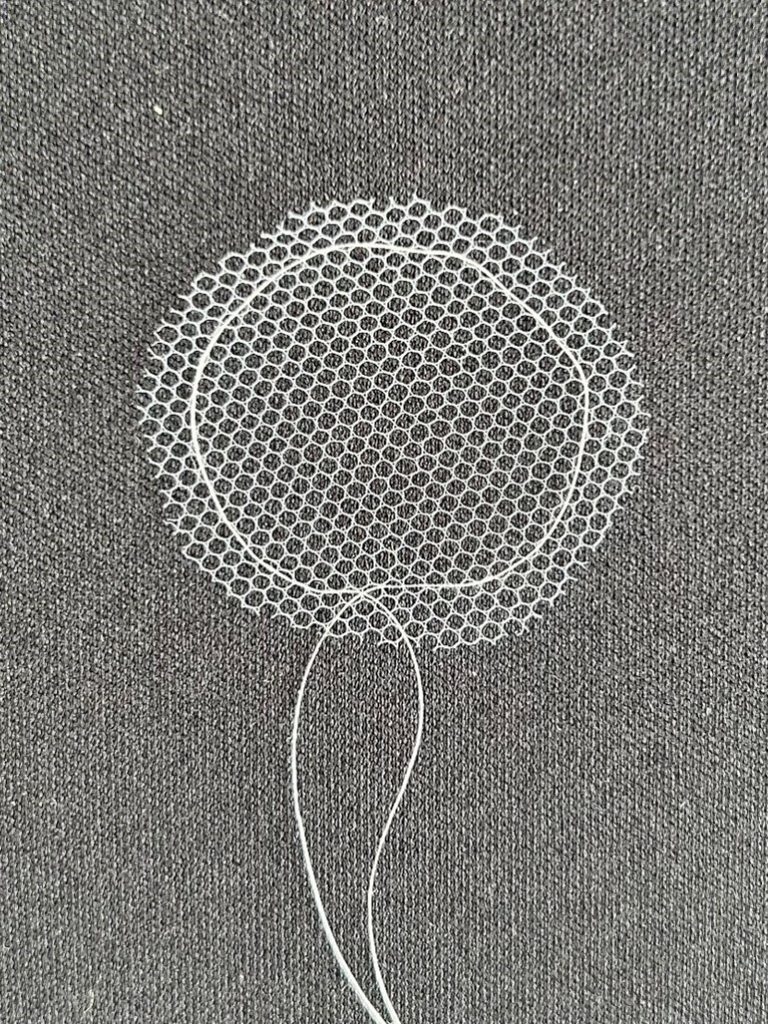

An example of the method that was used to cover the button; a tulle circle with a drawstring. Photo by author.

After conserving all the fragmented buttons with this method, they remained vulnerable. Therefore, a material was sought to act as a cover that would tie everything together and make it look like an actual button again. Both silk crepeline and tulle were considered. The downsides of silk crepeline are the fraying edges and the inability to drape the material over the filing. Tulle has the right properties of being transparent and mouldable, but a matching blue tone had to be found. For the treatment of the gauze sleeves in the same jacket, a large batch of tulle samples was ordered. Fortunately, there was a perfect blue sample in this mix that could be used for the buttons. A few different methods were tested to get a good result with the tulle overlays. The size of the circle was important since too much fabric led to bulging and a cover that was too tight deformed the filling during application. A thread was inserted a few millimetres from the edge of the tulle circle that would serve as a drawstring (fig. 5).

A detail of the buttons after being covered with tulle. The button in the middle is original. Photo by author.

The tulle was then laid on top of the new filling and centred. The thread was pulled to shape the cover around the filling. The string was tied around the base of the button multiple times and then tied off. This tulle cover as a final step gives the buttons an extra layer of protection and makes them blend in with the object.

I am very pleased with the results and maybe more buttonless buttons can be treated with a similar approach in the future!

Willemijn Bolderman, Intern, spring 2023.