Volume 111663_SKOBOK is perhaps not the crown jewel in the collection of funeral sermons from the Skolkloster Library. Bound in black cardboard and about the length and width of an A4 sheet of paper, it has certainly seen better days. The edges are worn and, until the intervention of paper conservator Fanny Stenback, the spine was completely missing in places. But to be fair, for a 300+ year old, it is doing pretty well.

Unusually, this volume is not a collection of sermons on various different people. Instead, it focuses soley on one man: Wilhelm Ludwig, Duke of Würtemberg (1647-1677). Wilhelms life was apperently interesting enough for 8 sermons, four engraved portraits of himself and his family, a large engraving of his coffin, and a family tree going back 5 generations. In his portrait, he appears in all the dignity of a fan-shaped lace ruff (that matches his father Eberhard’s), bountiful frizzy curls, and a tiny (almost inperceptible) moustache: what tragedy for the world to have lost such a scion of fashion and family at such a young age.

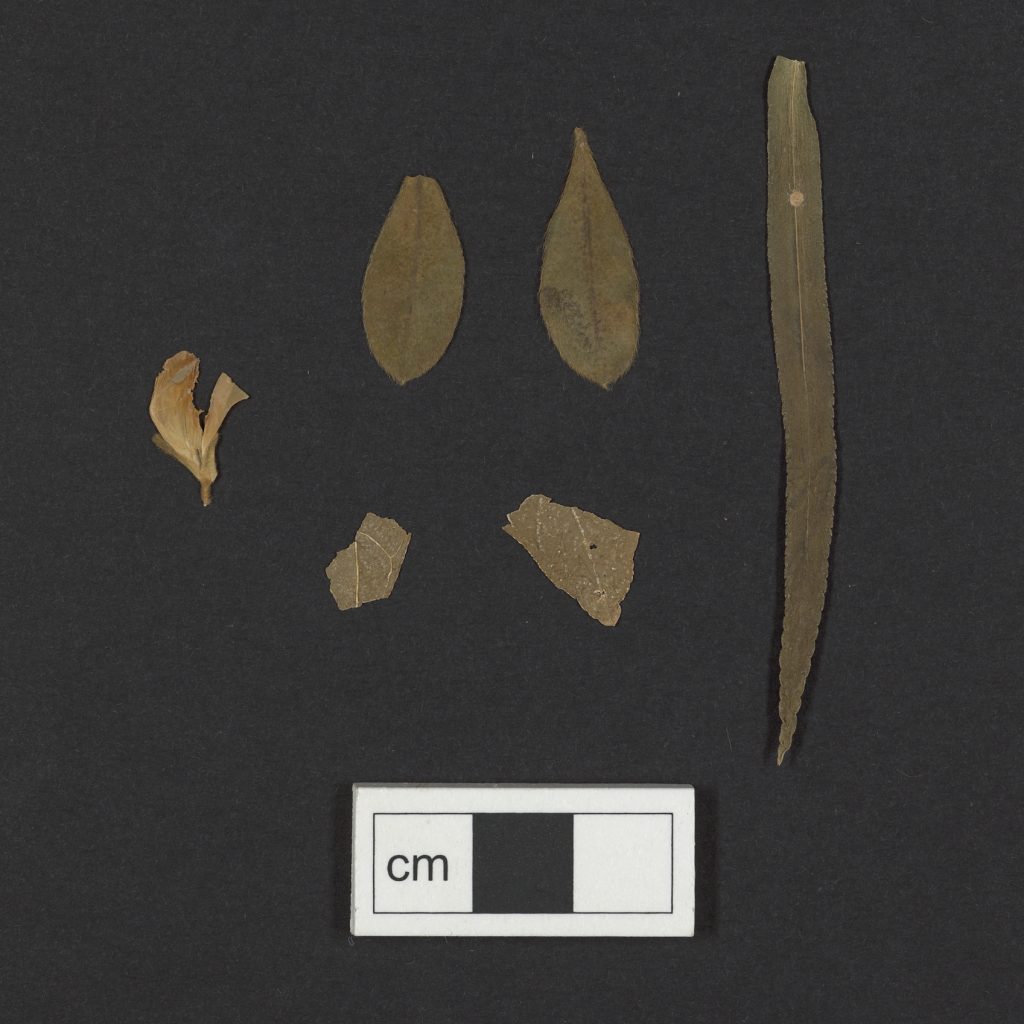

And yet despite the solomn dignity of this text, some later reader has done the unthinkable. They have used this book to press flowers. Flowers and leaves are not unusual things to discover in these volumes. They are large and heavy and infrequently referenced, so they make the perfect target for preserving plant life (and the occational housefly). These usually consist of just a single leaf – perhaps pressed, but just as easily, an unnoticed volunteer that has fallen on an unattended page or an impromptu bookmark never returned to. This volume, however, is different: there is a whole collection of different leaves, a flower, and purple petals plastered onto a page (not to mention the resulting vegetable stain that persists through several layers).

It is hard to say when these flowers were placed into this book or by whom. The funeral sermons were likely printed in 1677 and bound into a volume sometime after. This volume was then sold on in January of 1754 to Count Carl Gustaf Bielke for his collection at Salsta Castle, North of Uppsala. Yet barely had this book arrived when, in February, the Count died, passing his colleciton to Erik Brahe and Skolkloster Castle. The books relocated in the Spring of 1755, but alas, Erik Brahe also did not have very long to enjoy his newly expanded library. He died in July of 1756. As far as we can tell, these deaths are unrelated to this book – but we still wear gloves regardless.

Though we can’t pinpoint a specific culprit, have had more luck identifying the plant. Thanks to Biologist Erik Emanuelsson and the on-call biologist program at the Natural History Museum, we have identifications for at least two of them: The long thin leaf is a plant called sneezewort (Achillea ptarmica). This perennial flower of the daisy family is a native species widespread across Europe. It has little white flowers that bloom in the summer and the leaves can be used as an insect repellant. It can be eaten and apperently has a numbing, tingling effect in the mouth and can be used to relieve toothache or ulcers.

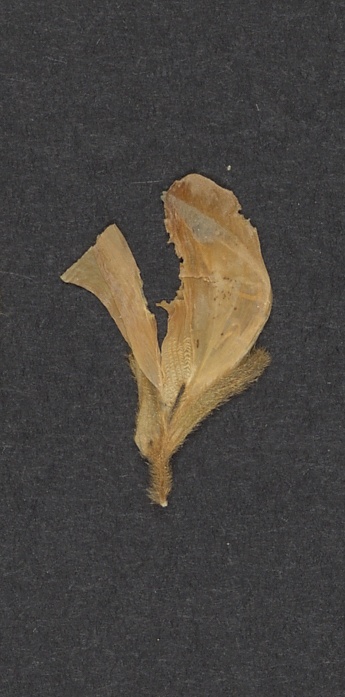

The small, pale flower however is not native – and is more likely to cause pain than relieve it. It is that familiar enemy of the Swedish gardener: the lupin! The European Yellow Lupin (Lupinus luteus) is a native of Southern Europe and the Mediterranian but it has been cultivated in Sweden for a long time.

So long, in fact, that Erik Emanuelsson was able to find a perfect twin of our pressed flower in ‘Münchenbergs Herbarium’ in the collection of the National History Museum. This gorgeous plant encyclopedia, compiled by Anton Christophersson Münchenberg (1680-1743) between roughly 1699 and 1702, is full of real pressed flowers that Münchenberg picked on Gotland and in the Academic garden in Uppsala. Not only is it a wonderful (and rarely preserved) historical example of a pre-Linnean herbal, but here it is, 300 years later, still a useful and effective reference guide!

Whether expanding the biography of a dead German Duke or helping identify centuries-old pressed flowers, these old books are still full unexpected treasures and delightful surprises. I can’t wait to see what falls out of them next!

Rosemary Hanson